The loud-minority internet and the half-life of outrage

What extends it, and how we might measure and mitigate it

It’s always been possible for small, intense minorities to sway a room. The internet industrialized that effect, and our own amplification - supported by handheld devices and infinite doom scrolling - sustains it. If we want healthier culture, capitalism, and politics, it helps to measure how fast outrage decays and work out ways to stop re-igniting it.

Human nature didn’t change. Infrastructure did. Our feeds reward high-arousal content - outrage, moralized language, all the performative highs and lows that we see every day online. That social feedback conditions us to produce more content that spikes, and the “spiral of silence” effects hide the silent majority. Edge takes start to look like consensus. It’s a reliable illusion, the first day extremes feel like “everyone”, when they’re a long way from that.

In boardrooms, newsrooms, politics, our daily lives, we keep treating initial intensity as truth. We manage the spike, but not the subsequent decay. We shouldn’t be asking “how loud is it today?”. A better question might be “how fast does this fade if we don’t keep feeding it?”

A better yardstick: the outrage half-life

We don’t have to guess whether a flare-up is a real movement or just a passing moment. We can watch how quickly things cool when nobody is adding anything new. Let’s call that cooling speed the outrage half-life: the time it takes for negative attention above the baseline to drop by half.

By baseline, I mean the normal level of negative attention something gets when nothing unusual is happening. it’s a background trickle of public complaints or critical posts; “my Amazon delivery was late” or “Dodge trucks suck”. In practice…we measure negative items, try to compute a calm-period median, and subtract that. What’s left, rising and falling, is excess negative attention, not total chatter.

So the natural cooling time - absent something that re-ignites things - is the base half-life (t½, base). But we’re rarely absent that re-ignition, quote-tweets, meme sharing, “coverage of the coverage” stories, drip-fed brand responses daily. These are maintenance events that stretch out that decay. And we can call that the amplification coefficient K.

Effective half-life = Base half-life x (1 + K)

If K = 0, then the story just fades away at its natural pace. But as K grows, then it lengthens the time between halvings (e.g. if t½, base is 1 day, and K is 4, then the effective half life is 5 days.

A couple of things to clarify…

t½, base varies depending on the event. Some topics will cool down in hours (someone’s outfit on the red-carpet at the Met Gala). Others might take days to cool down even if K = 0 (a major celebrity dies, a national policy change affects multiple people).

New facts are new shocks. If genuinely new information arrives (an investigation result is released, a lawsuit is filed), then we have to reset the clock and estimate a new half-life for the new epoch. K is a measure of amplification of old heat, not legitimate updates.

This is a gut-check metric, not lab science. I’ve used ChatGPT to help me determine something that we might use to guide judgement, not a rigorously tested way to end arguments.

American Eagle x Sydney Sweeney: an example of amplification in action

American Eagle’s “Sydney Sweeney has good jeans” campaign came out in late July. And we got the immediate backlash over the “genes/jeans” pun. The brand posted clarifications (“it’s just about jeans”). The story got reframed as a culture-war proxy. We had follow ups and comparisons to rival denim ads. We got multiple re-ignitions.

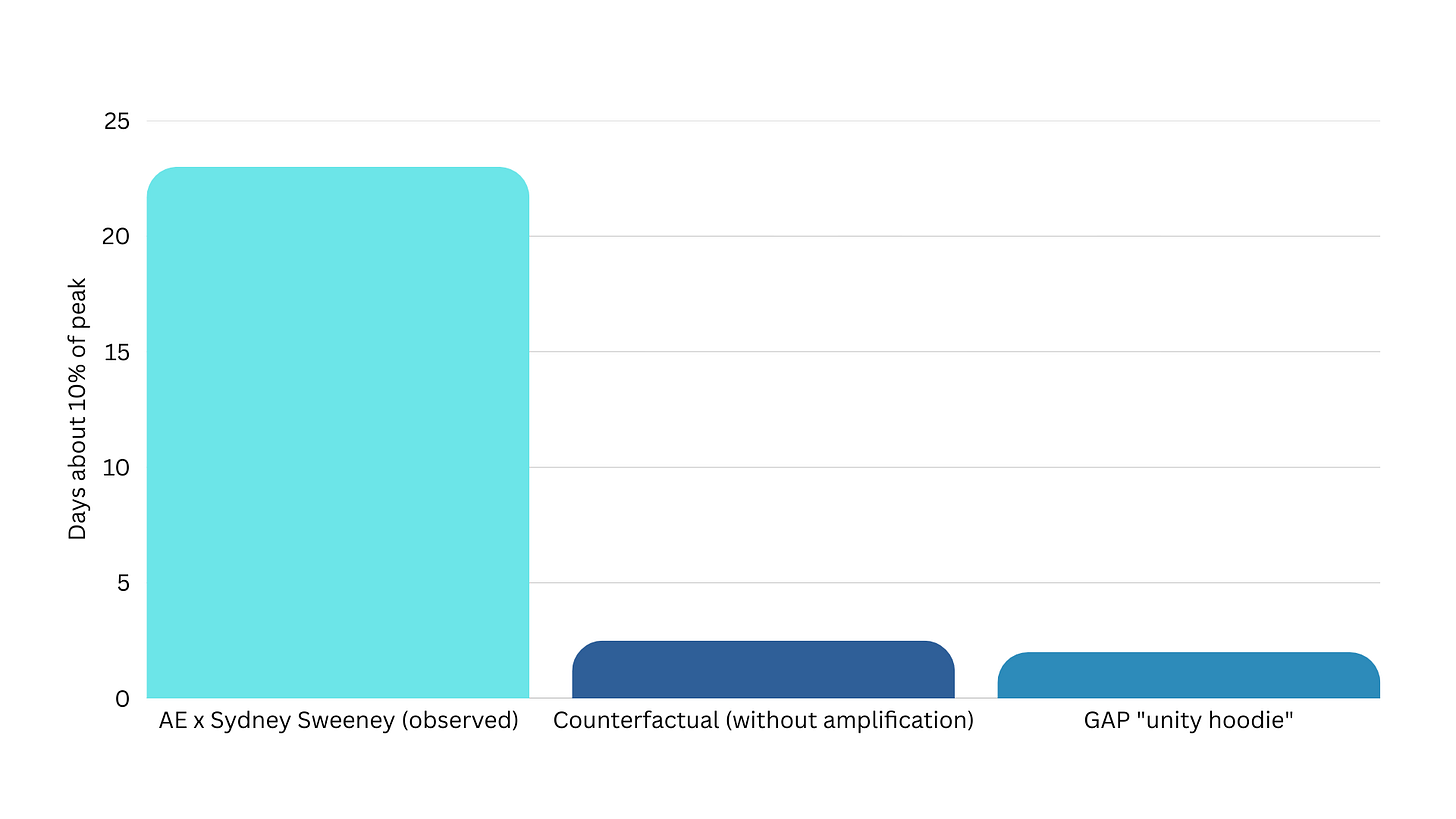

If we think of “meaningful public chatter” as anything above ~10% of baseline, that story stayed alive for roughly three weeks. Let’s say 23 days. The time to 10% is ~3.32 half-lives, which means an effective half-life ≈ 6.9 days. If we estimate a pretty conservative base half-life for an un-maintained brand flare up at ~12-18 hours, then we end up with K ≈ 8-13.

In plain English; all of our amplification kept a two-day story alive for three weeks.

GAP’s “unity hoodie”: the fast burn-out contrast

You might barely remember it now. GAP posted a red/blue “unity hoodie” tweet just after the 2020 Presidential election. People made fun of it, they deleted it within hours, it had a day or two of coverage, and then it faded away.

The story’s effective half-life was hours, not weeks. We were pretty close to K ≈ 0. A fast removal, nothing durable to hang a story on, and a short tail.

Our villain is amplification, not outrage

There are two forces working to lengthen the outrage half-life beyond what we might consider its natural decay. Algorithmic oxygen gives it an initial push, our ranking systems love high-arousal engagements, and they keep it going because the feeds treat a late quote-tweet the same as if it were fresh content. And our own human oxygen keeps the fire going. We recirculate the artifacts across multiple platforms, we “cover the coverage” in the news, and drip-fed statements can keep fueling the cycle.

The learning effects of our digital ecosystem mean that all of those likes and shares have taught us to express more outrage for longer. That’s why it’s so easy for there to be sparking “second waves” that catch on so quickly. These aren’t adding facts, they’re adding half-life.

Shortening the half-life (how can we reduce K?)

If we really care about getting better outcomes, we should be trying to manage the decay, not manage the spike.

Platforms could de-weight older posts unless new information is added. Screenshots and memes could be collected into a canonical threads, and require a “what’s new” note on re-shares after 24 hours. And plurality panel surveys could undermine the illusion we’ve created that “everyone” is mad.

Institutions might adopt a 72-hour rule, where they don’t reverse course or pivote with a “we hear you” message without estimating half-life and checking real-world tasks. Don’t feed the fire with a drip feed of statements, make a single, canonical update.

Press and media should minimize “coverage of coverage” stories. And if there are updates, offer them in a batch of corrections not a minute-by-minute churn.

You (all of us) could choose to not boost the second wave. If you’re not adding new context, try to keep quiet. Reward people who are explaining things over those who are posting dunks and gotchas. Mute the screenshot/meme farms and the rage-quoting accounts.

Design for the half-life, not the headline

The internet is really good at surfacing anger. And it’s really really good at maintaining it. All these stories have natural base half-life, some of them cool down in hours, some in days. But we manage to stretch some of those moments into months with our added amplification - K - re-shares with no new facts, drip-fed statements, coverage of the coverage.

If the base cool-down is short and nothing real is broken, we should work harder to let it end. If the half-life is stretching out, we can try to fix what’s actually broken (recognition, access, values, performance). Platforms, institutions, and people could all turn the oxygen down…if they wanted to.

Maybe with a greater awareness, a formula like this, we can be more aware. Not managing the spike, trying to manage the decay. If you’re not adding facts then you’re just adding to the half-life.

Further reading:

Brady, William J, et al. How social learning amplifies moral outrage expression in online social networks. Science Advances, 2021.

Huszár, Ferenc, et al. Algorithmic Amplication of Politics on Twitter. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science (PNAS), 2022.